Grey Matters

A digital resource for older adults experiencing changes to their memory and thinking

Grey Matters is an online resource that was co-designed with older adults and their whānau. Its purpose is to engage users in a conversation about ageing, with a particular focus on ideas and strategies for managing changes to memory and thinking. In addition to being an information resource, users can share stories and ‘Tips and Tricks’ for managing memory problems so that others can learn from their experience.

Client: Brain Research New Zealand

Team: Nicola Kayes, Guy Collier, Nick Hayes, Cassie Khoo

Contributors: Auckland District Health Board, University of Auckland, Otago University, Auckland University of Technology

My Role

As the primary researcher and project manager for this piece of work, I worked across the design process from front-end research to concept delivery. My role involved recruiting participants, facilitating workshops with users, collecting and analysing interview data, and working closely with the designers to generate, develop, and test design concepts. I also wrote the content for the website and made sure it had a consistent and friendly tone throughout the site.

Brief

Our brief was to design an online resource for older adults experiencing Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI). The site needed to meet the needs of both the person experiencing MCI and their family members. The client wanted the site to function as a platform of stories and strategies created by people experiencing memory problems.

Context

MCI is a relatively new diagnosis associated with a higher risk of dementia in adults over the age of 65. People with MCI often experience memory and thinking problems that are beyond what clinicians consider to be ‘normal’, yet aren’t severe enough to warrant a dementia diagnosis.

MCI is often seen to be a ‘transitional’ stage on the way to dementia, but the diagnosis does not guarantee that the person will experience further cognitive decline. Research shows that some people with MCI will improve while others remain the same. Therefore its clinical definition, use, value, and relationship to dementia are still debated among clinicians and researchers.

Process

The first phase of this project involved interviewing our users. We wanted to find out who they were, what they were most concerned about, and what tools and resources they currently used to manage changes to their memory and thinking.

With the help of staff from memory clinics at Auckland and Counties Manukau DHBs, I visited 28 people (or ‘users’) in total, a combination of those who had been formally diagnosed with MCI, some significant others and whānau, and others who had concerns about changes to their memory and thinking but no formal diagnosis.

We analysed this interview data and developed some concepts, which we took back to our users for feedback. We also ran a co-design workshop to enable users to generate their own ideas and contribute to the design process in an ongoing and iterative way.

Insights

We used some empathy mapping tools with our users to better understand their experiences of ageing and cognitive decline. During the co-design workshop, we learned that they had other pressing concerns about the realities of ageing. They talked about social isolation, loneliness, and feeling marginalised (“shut out - not relevant”) in a society that seemed to ignore older people and their needs.

We learned that ‘MCI’ wasn't as important as some of these broader issues, and reflected that building a website around the diagnosis was perhaps too narrow. Interview data also highlighted that people diagnosed with MCI were often unaware that they had been diagnosed in the first place. Even when they were aware, many people didn’t know what it meant or how significant it was. So while our brief was to design a website for ‘people with MCI’, it turned out that very few people thought this was a helpful diagnosis.

This was reflected in people’s ideas and suggestions for the website. Our workshop participants wanted reliable information about ageing and memory, health tips and advice, and also a digital space to connect with others and learn from their experiences. They weren’t so interested in the MCI label. They agreed that it would be useful to be able to share stories and strategies related to managing the challenges of advanced age. In response to their concern about terminology, we shifted our focus to ‘changes to memory and thinking’.

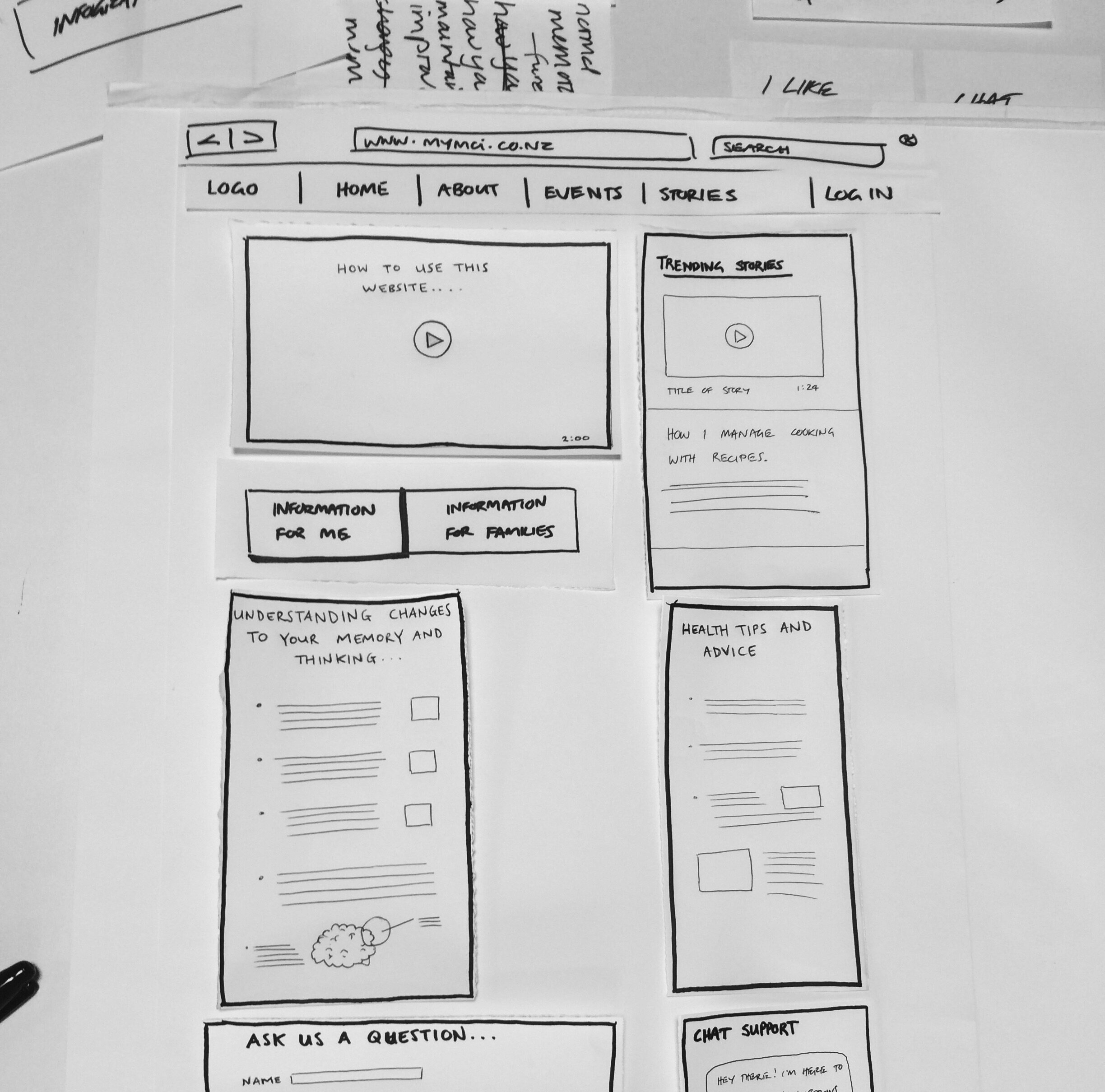

We developed some wireframes and used a card sorting exercise with a number of people to come up with our content hierarchy. We found that ‘information’ came out on top and ‘connecting and sharing’ came in as a close second. But it was our users response to the UX methods themselves that were most interesting.

Wireframes are used to establish the basic layout and functionality of a website before content and imagery is added. They are usually black and white so that the feedback from users at this stage is around layout and function rather than visual design or content. However, our users did not understand how the black-and-white wireframes in front of them corresponded to a website. It was too abstract for them. So we had to develop a higher resolution prototype before we could get their feedback.

Similarly, the card sorting exercise (another classic UX method) was very difficult for some of our users to perform due to their cognitive impairment. As one participant told us, “I can’t sort things or sequence information”. This was a reminder that UX methods sometimes have to be adapted to different user groups so as not to draw attention to their limitations.